Living with Colorectal Cancer—for One Day

Stories - Jul 13 2016

As part of the #ColorectalCancer1Day project, I spent a day in close contact with a cancer patient—learning from her, sharing stories, and reflecting on my own experience as a cancer survivor.

By Ginger Hanson, PhD

Monday started out like any other work day, but as I sat down and fired up my computer I heard the familiar “ding, ding” of my smartphone alerting me that I had a text. A small flurry of text notifications followed. I picked up my phone to see what the commotion was about—and then remembered that this was my day to be a “learner” in #ColorectalCancer1Day, a patient empathy experience conducted by an online community called Smart Patients.

In this novel program, researchers working in the area of colorectal cancer are paired for a single day with a patient receiving treatment for colorectal cancer. Through texts and emails with a patient “teacher” and a “colorectal cancer empathy kit” designed by patients to help simulate some of the side effects of colorectal cancer treatment, I would get to experience what my teacher experiences and feels on a daily basis.

I became aware of this opportunity through my work with the Patient Outcomes Research to Advance Learning (PORTAL) network, which has partnered with Smart Patients to bring this program to the research community. The Center for Health Research is a long-standing PORTAL member. My own involvement with the network started when I began working with my CHR colleagues Carmit McMullen and Mateo Banegas on a pilot grant exploring employment outcomes associated with colorectal cancer treatment. This issue is of great interest to me, given my research focus on the impact of workplace factors on health and health care utilization.

Connecting with Jennifer

In recent months, I’ve been poring over the colorectal cancer and employment literature while developing the pilot grant with my colleagues. I have also learned from personal experience more than I ever thought I would know about what it’s like to live with cancer. As a breast cancer survivor, I now bring a very personal perspective to my research.

But beyond my own experience and knowledge of the literature, I wanted to specifically understand the colorectal cancer experience on a more personal level—the daily hassles and the challenges of integrating treatment, work, and other life experiences. It was my good fortune that Jennifer, the patient I was paired with, was a wonderful teacher.

Jennifer’s life, like mine, is too full and varied to be defined by her cancer diagnosis and treatment. With two children, three stepchildren, and a full-time job, she has a complex life that requires integrating family, work, and life activities with her medical treatment. I learned that despite severe fatigue, she continued attending her children’s events and reading to them in bed. She also kept working at her job.

Each new thing I learned about Jennifer’s life led me to reflect on my own experience. For example, her employer allows her to telecommute and work flexible hours—benefits that are critical to her ability to keep working. She is better able to manage common treatment side effects such as fatigue, nausea, and diarrhea when she has access to the comfortable amenities of home and can work during the time of day she feels best. She was motivated to stay at her job because her team needed her. For me, the motivation came from my enjoyment of my work and my desire to maintain some normalcy as I dealt with my illness.

Each new thing I learned about Jennifer’s life led me to reflect on my own experience. For example, her employer allows her to telecommute and work flexible hours—benefits that are critical to her ability to keep working. She is better able to manage common treatment side effects such as fatigue, nausea, and diarrhea when she has access to the comfortable amenities of home and can work during the time of day she feels best. She was motivated to stay at her job because her team needed her. For me, the motivation came from my enjoyment of my work and my desire to maintain some normalcy as I dealt with my illness.

In addition, her husband has flex-time at work, allowing him to schedule his starting and stopping time each day so that he can be home when their kids get home from school. This provided another positive example to add to my own about the importance of integrating work and non-work while going through treatment and some of the tools needed to make that possible.

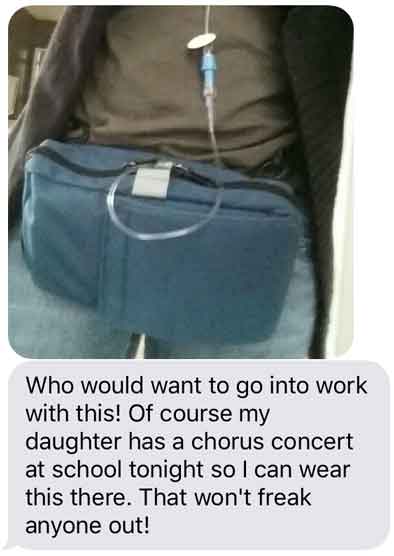

Another key learning for me was the mental and emotional toll of Jennifer’s colorectal cancer treatments. She needed to be hooked up to a fanny pack that slowly dispensed chemotherapy over a 24-hour period. As the date of her daughter’s choral performance approached, she worried about the unwanted attention this device might attract—but the event was too important to miss.

Jennifer’s challenge with avoiding attention reminded me of how I felt about losing my hair. I had been excited to go bald at first, thinking it would feel very empowering. However, I soon learned that it would be an invitation to perfect strangers to come up to me and tell me how cancer had affected them, or to express concern for my well-being. After a week, the emotional toll was too much and I began wearing a hat so I could pass as “normal.”

Jennifer’s challenge with avoiding attention reminded me of how I felt about losing my hair. I had been excited to go bald at first, thinking it would feel very empowering. However, I soon learned that it would be an invitation to perfect strangers to come up to me and tell me how cancer had affected them, or to express concern for my well-being. After a week, the emotional toll was too much and I began wearing a hat so I could pass as “normal.”

Jennifer did not have an ostomy bag, but as part of the empathy experience, SmartPatients suggested that I tape a large plastic sandwich bag with about 8 ounces of water to my abdomen. While no one commented on it, I felt self-conscious about it all day and found myself frequently self-monitoring to make sure I was presenting as normal. The bag leaked twice, giving me just a hint of the inconvenience (and, perhaps, embarrasment) that some colorectal cancer patients must endure.

A meaningful experience with lasting impact

The #ColorectalCancer1Day experience was very powerful for me. My personal interactions with Jennifer gave me a deeper understanding of the challenges that colorectal cancer patients face in managing their multiple roles and responsibilities, and the importance of workplace supports in helping them do this successfully. And without this experience, I wouldn’t have had a sense of what it feels like to wear a chemotherapy administration device in public or to care for an ostomy bag at work.

These learnings will be instrumental for me as I begin work on the new pilot study my colleagues and I have been awarded through PORTAL to study the impact of colorectal cancer on employment and financial outcomes. Our goal is to develop interventions to improve these outcomes for patients. In addition, the new knowledge I acquired from Jennifer about her treatments and their side effects will enrich my scientific writing and ground it more thoroughly in patients’ lived experience.